Okay, real talk—nothing is more frustrating than eating like a bird, sweating it out at the gym, and then stepping on the scale only to see… nothing. Like, literally nothing. The number just sits there, mocking you.

I get it. You’ve been told a million times that weight loss is simple math: eat less than you burn, and boom—the pounds should just melt away, right? That’s the whole “calories in, calories out” thing everyone talks about. And technically, yeah, if you’re in a calorie deficit (meaning you’re consuming fewer calories than your body needs), your body should tap into stored energy—aka your fat stores—to make up the difference. Science says so!

But here’s the thing: your body isn’t a calculator. It’s more like a super complicated, moody computer that doesn’t always follow the instruction manual. Biology is messy, and there are literally dozens of sneaky factors that can throw a wrench in your weight loss plans, even when you’re doing everything “right.”

Research calls this the “bioenergetic paradox”—the phenomenon where predicted weight loss and actual weight loss don’t match up. But this isn’t a failure of thermodynamic principles. Your body is a dynamic system that employs a whole suite of metabolic, hormonal, and behavioral adaptations to defend your current weight against what it perceives as starvation. Yeah, your body literally fights back.

So if you’ve been asking yourself, “Why am I not losing weight in a calorie deficit?”—friend, you’re in the right place. I’m breaking down 12 science-backed (but totally relatable) reasons why your weight loss might be stalling. Some are obvious, some are hidden, and honestly, some are just plain annoying. But understanding them? That’s your first step to actually breaking through that plateau.

Let’s dive in.

- The Foundation of Failure: You're Not in a True Deficit

- Metabolic and Hormonal Adaptations (Adaptive Thermogenesis)

- Metabolic Adaptation (The Dreaded Plateau)

- The Leptin-Driven Neuroendocrine Cascade

- Mitochondrial Efficiency: Your Cells Get Thrifty

- The Drop in Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT)

- The Exercise Paradox: Why More Activity Doesn't Always Mean More Weight Loss

- The Constrained Energy Model

- Exercise Compensation in Real Numbers

- Walking vs. Running: Not All Cardio Is Created Equal

- Prioritizing Quantity Over Quality

- Lifestyle Factors That Mask Fat Loss

- Water Retention and Scale Inconsistency

- Assessing Progress Beyond the Scale

- Medical Conditions or Medications

- Precision Strategies for Breaking Through Plateaus

- Conclusion: Sustainability is the Secret

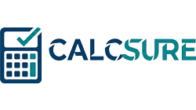

The Foundation of Failure: You’re Not in a True Deficit

Before we get into the fancy science stuff, let’s start with the most common culprit—and I say this with love—you might not actually be in a calorie deficit. I know, I know. You’re thinking, “But I’m eating so little!” But hear me out.

Inaccurate Calorie Tracking and Portion Misestimation

Here’s a fun fact that’s not actually fun: most of us are terrible at estimating how much we’re eating. Like, really terrible. Studies show that people can underestimate their calorie intake by 400-500 calories per day. That’s basically a whole meal!

And it gets worse. Research using doubly labeled water—the gold standard for measuring energy expenditure—revealed something called “flat-slope syndrome.” Basically, people with higher BMIs tend to under-report their food intake significantly. This isn’t just forgetfulness; it’s something called “social desirability bias,” where we subconsciously edit what we record to look better, even just to ourselves.

Then there’s “reactivity bias”—the fact that just knowing you’re tracking your food changes how you eat. Studies show that reported energy intake can be as much as 16% lower than actual expenditure simply because people eat differently when they know they’re being monitored.

You might be super diligent about logging your grilled chicken and veggies at lunch, but then conveniently forget about the handful of almonds you grabbed at 3 PM, the few bites of your kid’s mac and cheese, or that “small” serving of pasta that was actually three servings.

And don’t even get me started on eyeballing portions. That “tablespoon” of peanut butter? Yeah, it’s probably closer to three tablespoons. Those handful of crackers? More like a serving and a half.

Here’s what to do: Get yourself a digital food scale—I’m talking like $15 on Amazon. Weigh your food for at least a couple weeks. You don’t have to do this forever (because who has time for that?), but it’ll seriously calibrate your brain to what portions actually look like. Modern research even uses machine learning to identify and correct misreported food entries, achieving over 82% accuracy in reclassifying under-reported data. Track everything in an app, and I mean everything. Be honest with yourself. You’re not trying to win a “who can eat the least” contest with your fitness app—you’re trying to get real data.

Hidden Calories in Oils, Drinks, and Condiments

Oh man, this is where things get sneaky. You know what has a ton of calories? Oil. Like, a scary amount. Just one tablespoon of olive oil (which sounds healthy, right?) packs about 120 calories. When you’re cooking, it’s super easy to drizzle way more than you think.

And condiments? That ketchup, BBQ sauce, salad dressing, mayo—they add up fast. A couple tablespoons here and there, and suddenly you’ve added 200-300 calories to your “healthy” salad.

Then there’s the liquid calorie trap. That morning latte with flavored syrup and whole milk? Could be 300+ calories. The glass (or three) of wine at night? Alcohol has about 7 calories per gram—almost as much as fat! And here’s the kicker: these liquid calories don’t fill you up at all, so you’ll still eat the same amount of food on top of them.

Here’s what to do: Track every single thing that goes in your mouth. Every splash of creamer, every spray of cooking oil, every “just a taste” when you’re cooking dinner. Use measuring spoons for oils and dressings. And maybe swap some of those calorie-loaded beverages for water, unsweetened tea, or black coffee. I’m not saying never have a drink, but be aware of what you’re actually consuming.

Overestimating Calories Burned via Exercise Trackers

Your Fitbit says you burned 600 calories during that spin class? Yeah… probably not. Hate to break it to you, but fitness trackers and cardio machines are notoriously bad at estimating calorie burn. Research shows they can overestimate by 20-50% or even more—with some trackers showing error rates as high as 40%.

So if you’re eating back all those “earned” calories based on what your watch tells you, there’s a good chance you’re actually wiping out your calorie deficit entirely or even putting yourself into a surplus.

Here’s what to do: Take those calorie burn estimates with a huge grain of salt. If you want to eat a little more on workout days, cool—but maybe eat back like half of what your tracker says, max. Or better yet, don’t eat back exercise calories at all and just see them as a bonus contribution to your deficit.

The Resting Metabolic Rate Calculation Crisis

Even if you’re tracking perfectly, you still need to know your starting point—your Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR), which is the calories you burn just existing. Most of us use online calculators for this, but here’s the problem: these formulas are wildly inaccurate for individuals.

The Mifflin-St Jeor equation—currently the gold standard—only falls within 10% of measured values for about 56% of people. That means almost half of us are getting numbers that are significantly off. For someone with a measured RMR of 2,000 calories, a 10% error represents 200 calories—potentially 40% of a typical 500-calorie deficit!

The breakdown of popular equations:

- Mifflin-St Jeor: Most accurate (56.4% within 10% of actual), but still misses for almost half the population

- Harris-Benedict: Tends to overestimate by 10-15%, especially in older adults where it can predict 1607-1625 kcal/day when actual is closer to 1451 kcal/day

- WHO/FAO/UNU: Over-predicts in males and overweight individuals

- Owen: Wildly unreliable, under-predicting for 39.2% and over-predicting for 51.9%

And those “activity multipliers” (1.2 for sedentary, 1.55 for moderately active)? They often don’t reflect modern lifestyles and assume exercise is purely additive to your baseline—which, as we’ll see, isn’t how your body actually works.

Metabolic and Hormonal Adaptations (Adaptive Thermogenesis)

Alright, now we’re getting into the stuff that makes weight loss really tricky—the fact that your body literally fights back when you try to lose weight. Fun times.

Metabolic Adaptation (The Dreaded Plateau)

So here’s something frustrating: the longer you’re in a calorie deficit, the more your body tries to sabotage you. It’s called metabolic adaptation or adaptive thermogenesis, and basically, your body thinks you’re starving (even if you’re just trying to fit into your jeans from college).

When you eat less, especially for weeks or months, your metabolism slows down to conserve energy. It’s a survival mechanism from our caveman days when food scarcity was a real threat. Your body’s like, “Oh no, famine! Better hold onto every calorie!”

Here’s where it gets really interesting—and frustrating. Studies show that after losing 10% or more of your body weight, your total 24-hour energy expenditure can drop by 20% to 25%. But here’s the kicker: this is 10-15% MORE than what you’d expect from just having less body mass to maintain. Your body isn’t just burning fewer calories because you’re smaller—it’s actively suppressing your metabolism beyond what’s mathematically necessary.

Plus, as you lose weight, your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)—the calories you burn just existing—naturally decreases because you literally have less body mass to maintain. A smaller body needs fewer calories to run, period. This accounts for about 60-75% of the calories you burn daily.

So even if you’re eating the same amount and doing the same workouts, you might stop losing weight because your body has adjusted to your new normal. This is the dreaded plateau that makes people want to throw their scales out the window.

The Leptin-Driven Neuroendocrine Cascade

The mastermind behind all this metabolic slowdown? A hormone called leptin. Think of leptin as your body’s fuel gauge—it’s produced by your fat cells and tells your brain how much energy is in storage.

As you lose fat, your leptin levels drop. Your brain’s hypothalamus detects this and freaks out, thinking you’re starving. It triggers a whole cascade of hormonal changes to slow you down and make you hungrier:

What happens after losing ≥10% of body weight:

- TSH (Thyroid Stimulating Hormone): Drops by 18%

- T3 (Triiodothyronine): Decreases by 7%—this is your active thyroid hormone that controls metabolic rate

- T4 (Thyroxine): Falls by 9%

- Sympathetic Nervous System activity: Plummets by 40%—meaning your heart rate slows and your muscles work more efficiently (burning fewer calories)

- Parasympathetic Nervous System activity: Increases by 80%—putting you in maximum energy conservation mode

And here’s proof that leptin is the puppet master: when researchers gave dieters leptin replacement to bring their levels back to pre-weight-loss amounts, these metabolic adaptations reversed. The thyroid perked back up, metabolism increased, and the body stopped fighting so hard against weight loss.

Mitochondrial Efficiency: Your Cells Get Thrifty

At the cellular level, your mitochondria—the powerhouses of your cells—actually become more efficient when you’re dieting. Normally, when you have plenty of food, your mitochondria are kind of wasteful. They let energy “leak” out as heat through a process called proton leak, which can account for 20-30% of your resting metabolic rate.

But when calories are scarce, your body downregulates proteins called uncoupling proteins (UCP-1 and UCP-3) that normally allow this energy leakage. The result? Your mitochondria squeeze every last bit of ATP (energy) out of the food you eat, wasting less as heat. You become a metabolically efficient machine—which is great for survival, but terrible for weight loss.

The Drop in Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT)

Here’s a weird one: when you’re dieting, you probably move less throughout the day without even realizing it. This is called Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis, or NEAT—basically all the calories you burn doing everyday stuff like walking to your car, doing laundry, fidgeting, standing while you cook, etc.

NEAT is hugely variable between people, ranging from 100 to 800 calories per day. When you’re in a calorie deficit, your body gets sneaky and subconsciously reduces these little movements to save energy. You might take the elevator instead of stairs, sit more, fidget less, take fewer steps around the house. It’s totally unconscious, but it can add up to hundreds of fewer calories burned per day.

In one study of older men doing an 8-week training program, NEAT dropped by a whopping 62%—from 571 to 340 calories per day. That’s a 231-calorie reduction that completely offset much of their exercise!

Here’s what to do: Be intentional about staying active throughout the day. Set hourly reminders to stand up and move. Take phone calls standing or walking. Park farther away. Take the stairs. Fidget more (hey, it counts!). Get a step counter and try to maintain your daily step count even on rest days. Basically, find ways to keep your NEAT up even when your body’s trying to conserve energy.

The Exercise Paradox: Why More Activity Doesn’t Always Mean More Weight Loss

Look, I’m all for exercise—it’s amazing for your health, mood, strength, and longevity. But here’s something that might blow your mind: adding exercise to your routine doesn’t increase your total daily calorie burn as much as you’d think. In fact, for some people, it barely increases it at all.

The Constrained Energy Model

We’ve always been told that energy expenditure works like this: your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE) = your Resting Metabolism + your Activity. So if you add a 400-calorie workout, your TDEE should go up by 400 calories, right?

Wrong. Or at least, not for everyone.

Enter the “Constrained Energy Model,” which is backed by fascinating research on human energetics. This model suggests that your TDEE doesn’t increase linearly with activity. Instead, at higher levels of physical activity, your total daily energy expenditure plateaus. Your body adapts by reducing energy spent on other stuff—like immune function, reproductive processes, cell repair, and yes, NEAT.

Evidence for this comes from studies of hunter-gatherer populations who are active all day long. Their TDEE? Pretty much the same as sedentary Westerners. Their bodies have adapted by being more efficient with non-exercise processes.

In a 24-week exercise intervention study, 48% of participants showed significant “exercise-related energy compensation”—meaning their increase in TDEE was way less than the calories burned during exercise. And this happened even when their sedentary time didn’t change, suggesting internal metabolic shifts were at play.

Exercise Compensation in Real Numbers

The “Midwest Exercise Trials” tracked people doing supervised exercise programs and measured actual changes in total daily energy expenditure versus predicted changes. The results were eye-opening:

- Men were prescribed exercise burning about 668 calories per day

- Their actual TDEE only increased by 371 calories per day

- That’s a 45% compensation rate—almost half the exercise calories disappeared!

For weight loss, this meant participants only lost about 50% of the predicted amount based on their exercise volume.

Why does this happen? Multiple reasons:

- NEAT drops (as we discussed)

- Your body becomes more efficient at performing the exercise itself over time

- Other metabolic processes slow down to conserve energy

- You might eat more (either consciously or unconsciously)

Here’s what to do: Don’t rely solely on exercise for weight loss. Use it as a tool for health, strength, and maintaining muscle mass, but know that you can’t out-exercise a bad diet (or even a moderately good diet if portions are off). The real magic happens in the kitchen.

Walking vs. Running: Not All Cardio Is Created Equal

Okay, so if exercise compensation is real, does it matter what type of cardio you do? Turns out, YES. And the difference between walking and running is pretty dramatic.

A massive study following over 15,000 walkers and 32,000 runners for 6.2 years found that running produced significantly greater weight loss per unit of exercise than walking—especially in people with higher BMIs. For those in the highest BMI category, running resulted in 90% greater weight loss per MET-hour than walking.

Why such a big difference? Let me break it down:

The Hormonal Story:

- Ghrelin (the hunger hormone): Running suppresses it by about 25% for up to 120 minutes after exercise. Walking? May actually increase it by 12%.

- Peptide YY (satiety hormone): Running elevates it by about 40%. Walking causes minimal or no change.

- The result: Runners naturally eat less after exercise, while walkers often feel hungrier.

The Calorie Compensation Story:

Controlled studies show that:

- Walkers offset about 28% of their exercise calories through increased food intake

- Runners only offset about 11%

So even though walking is gentler and more sustainable for many people, it comes with a built-in compensation mechanism that can seriously undermine weight loss efforts.

The Afterburn Effect (EPOC):

EPOC stands for Excess Post-Exercise Oxygen Consumption—basically, the extra calories you burn after exercise while your body recovers.

When covering the same distance (let’s say 1600 meters):

- Walking (86 m/min): Burns 463 kJ including minimal EPOC (about 7 extra calories)

- Running (160 m/min): Burns 664 kJ including significant EPOC (about 37 extra calories)

Running’s metabolic rate elevations can persist for 120 minutes post-exercise, while walking’s EPOC typically returns to baseline within 10 minutes. That’s an EPOC effect up to 500% greater for running.

Biomechanical Efficiency:

Running requires greater vertical displacement and faster ATP synthesis. While running a mile only burns 10-30% more than walking a mile, it does so in half the time. Plus, at speeds close to your maximum walking pace, walking becomes incredibly inefficient—sometimes even more energy-costly than running!

The Bottom Line: If your goal is weight loss and you’re physically able, incorporating some running or higher-intensity intervals can be way more effective than steady-state walking. But if walking is all you can do (due to injury, fitness level, or preference), that’s totally fine—just be extra vigilant about not eating back those exercise calories.

Prioritizing Quantity Over Quality

Look, I’m all for the “CICO is king” mindset to some extent, but here’s the thing: not all calories are created equal when it comes to how your body responds to them.

If you’re hitting your calorie target but living on processed junk—think sugary cereals, white bread, packaged snacks, fast food—your body’s gonna react differently than if you’re eating whole, nutrient-dense foods. Ultra-processed foods mess with your hunger hormones, can cause inflammation, and literally make you want to eat more. They don’t satisfy you the way whole foods do.

Plus, when you’re not getting enough protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals, your body sends out “I’m still hungry” signals even if you’ve technically eaten enough calories. It’s looking for nutrition, not just energy.

Here’s what to do: Focus on whole foods as much as you can—lean proteins, fruits, veggies, whole grains, healthy fats. These foods keep you fuller longer, provide the nutrients your body actually needs, and don’t trigger the same kind of overeating response that processed stuff does. You don’t have to be perfect, but aim for that 80/20 balance.

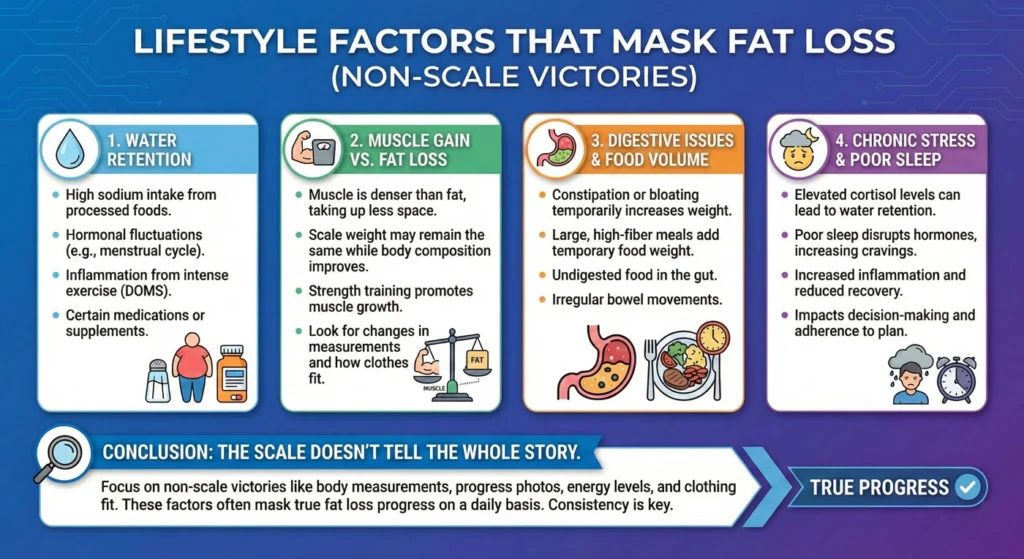

Lifestyle Factors That Mask Fat Loss

Sometimes it’s not even about the food—it’s about everything else going on in your life that’s messing with your weight loss.

Increased Stress Levels and Cortisol

Let’s talk about stress. And honestly? Dieting itself is stressful. You’re constantly thinking about food, restricting what you can eat, worrying about the scale—it’s a lot.

Research has shown that both monitoring your caloric intake AND restricting calories to 1200/day significantly increase your total cortisol output. When you’re chronically stressed, your body pumps out cortisol (the stress hormone). And cortisol is basically the worst wingman for weight loss.

Here’s what cortisol does:

- Makes you hungrier (especially for high-calorie comfort foods)

- Encourages your body to store fat (particularly around your belly)

- Can slow down your metabolism

- At high levels, stimulates mineralocorticoid receptors, leading to significant sodium and water retention

That last one is huge. Cortisol-mediated water retention can create a persistent “masking” effect on the scale that lasts for weeks, making it look like you’re not losing fat when you actually are. Then, when you finally take a maintenance break or stress decreases, you get a sudden “whoosh” of weight loss as the water releases.

Plus, stress often leads to emotional eating. You know, those nights when you’re like, “I had a terrible day, I deserve this entire pizza.”

Here’s what to do: Find ways to manage stress that don’t involve food. Try yoga, meditation, deep breathing, going for walks, journaling, hanging out with friends, or whatever helps you chill out. Seriously, managing stress might be one of the most underrated weight loss strategies out there.

Poor Sleeping Habits

If you’re skimping on sleep, you’re basically sabotaging yourself. Sleep deprivation messes with your hunger hormones in a big way—it increases ghrelin (which makes you hungry) and decreases leptin (which makes you feel full).

When you’re tired, your brain literally craves high-calorie, sugary, fatty foods for quick energy. Plus, you don’t have the mental clarity or willpower to make good choices when you’re exhausted. It’s like trying to drive with one eye closed.

Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. I know, easier said than done, but it really matters.

Here’s what to do: Make sleep a priority. Keep your bedroom cool and dark, establish a bedtime routine, cut off screens an hour before bed, avoid caffeine after 2 PM. Treat sleep like the important recovery tool it is, not as something you can sacrifice when you’re busy.

Hormonal Fluctuations (Menstrual Cycle, Menopause)

Ladies, this one’s for us. If you have a menstrual cycle, your weight is going to fluctuate throughout the month. It just is. Hormonal changes—especially the week or so before your period—can cause water retention, bloating, and temporary weight gain of several pounds.

This doesn’t mean you’re not losing fat. It just means your hormones are doing their thing and holding onto some extra water. It’s totally normal and will whoosh off after your period starts.

And if you’re going through menopause? Yeah, that’s a whole other challenge. Metabolism naturally slows down, and hormonal changes can make it harder to maintain or lose weight.

Here’s what to do: Track your cycle and your weight together so you can see the patterns. Don’t freak out about scale fluctuations during certain times of the month. If you’re menopausal, focus on building or maintaining muscle through strength training—this helps counteract some of the metabolic slowdown.

Water Retention and Scale Inconsistency

Here’s a truth bomb: the number on the scale doesn’t just reflect your fat stores. It reflects everything in your body—water, food in your digestive system, muscle, bone, organs, the works.

Your weight can fluctuate by several pounds from day to day (or even hour to hour) based on how much water you’re retaining, how much sodium you ate yesterday, whether you’ve pooped yet (sorry, but it’s true), how many carbs you ate (carbs hold onto water), whether you did a hard workout (inflammation and water retention), and so much more.

You could be losing fat consistently but the scale doesn’t show it because of these fluctuations.

Glycogen-Water Binding and “Refeed” Spikes

Let’s talk about glycogen—your body’s storage form of glucose. Glycogen is stored in your liver and muscles, and here’s the important part: each gram of glycogen holds onto approximately 3 to 4 grams of water.

On a low-carb or calorie-restricted diet, your glycogen stores get depleted. This is why you see rapid weight loss in the first week—you’re losing glycogen and all the water it was holding. Conversely, a single high-carb or high-calorie “cheat meal” can rapidly replenish these stores.

If you replenish 500g of glycogen, you’ll simultaneously gain 1.5 to 2.0kg (3-4 pounds) of water weight—potentially erasing weeks of scale progress in just 24 hours. But you haven’t gained fat! It’s just water.

Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage and Inflammation

When you start a new workout routine or increase intensity, you cause microscopic tears in your muscle fibers. This is actually good—it’s how muscles grow stronger. But it also triggers an inflammatory response:

The timeline:

- 1-24 hours: Neutrophils (white blood cells) infiltrate to clear cellular debris

- 24-48 hours: Macrophages migrate in, secreting cytokines that attract more fluid

- Result: Local edema (swelling) in the muscle tissue

This exercise-induced muscle damage (EIMD) can result in a gain of 1-3 pounds on the scale that persists as long as your muscles are repairing and adapting. For someone in a deficit losing 1-2 pounds of fat per week, this fluid weight can perfectly offset your fat loss, creating a frustrating “flat line” on the scale.

Here’s what to do: Weigh yourself at the same time each day under the same conditions—like first thing in the morning after using the bathroom, before eating or drinking. Better yet, track your weekly average weight instead of obsessing over daily numbers. Look at trends over weeks and months, not day-to-day changes. And drink plenty of water—paradoxically, staying well-hydrated actually helps reduce water retention.

Assessing Progress Beyond the Scale

The scale is just one metric, and honestly? It’s kind of a crappy one when you’re trying to change your body composition.

Gaining Muscle (Body Recomposition)

Here’s something cool: you can be losing fat and gaining muscle at the same time, especially if you’re new to strength training or getting back into it after a break. This is called body recomposition.

But here’s the thing—muscle is denser than fat. So if you’re building muscle while losing fat, the scale might not move much, or it might even go up slightly, even though you’re getting leaner and your clothes are fitting better.

This is actually a good thing! Muscle is metabolically active tissue, meaning it burns calories even at rest. More muscle = higher metabolism. But if you’re only looking at the scale, you might think you’re failing when you’re actually succeeding.

Here’s what to do: Use other metrics to track progress. Take measurements (waist, hips, thighs, arms). Take progress photos in the same lighting and poses every few weeks. Pay attention to how your clothes fit. Track your strength gains in the gym. Notice your energy levels. These are all better indicators of body composition changes than the scale alone.

Medical Conditions or Medications

Sometimes, despite doing everything right, there’s an underlying issue making weight loss really difficult. This is where things get clinical.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and Metabolic Resistance

PCOS is a complex hormonal disorder that affects metabolic function in ways that create serious resistance to weight loss. Women with PCOS often have:

- Hyperinsulinemia: Elevated insulin levels that inhibit hormone-sensitive lipase (the enzyme that breaks down fat) and actively promote fat storage

- Insulin Resistance: Even “lean PCOS” phenotypes can have significantly impaired glucose metabolism

- Adipocyte Hypertrophy: Enlarged fat cells that are strongly correlated with insulin resistance, independent of total body fat percentage

- Reduced GLUT-4: Impaired glucose uptake into muscle and fat cells

- Low Adiponectin: A hormone that normally improves insulin sensitivity—it’s downregulated in PCOS

- Elevated Leptin: Often secondary to hyperinsulinemia, contributing to leptin resistance

What this means in plain English: if you have PCOS, your body is biochemically resistant to releasing stored fat, even in a legitimate calorie deficit. The enlarged fat cells literally don’t want to shrink, and your insulin levels are actively working against lipolysis (fat breakdown).

Hypothyroidism and Subclinical Thyroid Dysfunction

Thyroid disorders are particularly prevalent in women with PCOS and those struggling with weight loss. Your thyroid hormones are essential for controlling your metabolic rate—they’re like the gas pedal for your metabolism.

Subclinical hypothyroidism (elevated TSH with normal T4) is associated with a three-fold higher risk in women with PCOS. Even mild thyroid dysfunction can drop your metabolic “floor,” making a standard 500-calorie deficit insufficient for meaningful fat loss.

Remember that adaptive thermogenesis cascade we discussed earlier? If you already have thyroid issues, the diet-induced suppression of thyroid hormones is even more pronounced, creating a double-whammy effect.

Other Medical Conditions

Conditions like Cushing’s syndrome, certain medications (antidepressants, corticosteroids, some diabetes medications, blood pressure meds, hormonal birth control), and insulin resistance can all seriously affect your weight and how your body responds to a calorie deficit.

Here’s what to do: If you’ve been consistently in a deficit for several weeks, tracking accurately, sleeping well, managing stress, and still nothing is happening—talk to your doctor. Get your thyroid checked (TSH, free T3, free T4). Ask about insulin resistance testing. Discuss your medications. Look into whether PCOS or other hormonal issues might be at play. This isn’t giving up; it’s being smart and getting the support you need.

Precision Strategies for Breaking Through Plateaus

Okay, so you’ve identified what might be holding you back. Now what? Here are some advanced strategies to actually get things moving again.

Implement Strength Training and High Protein Intake

If you’re not already doing strength training, start. Like, yesterday. Building and maintaining muscle is crucial for losing weight sustainably because muscle tissue helps protect your metabolism from slowing down too much.

When you’re in a calorie deficit, your body can break down muscle for energy if you’re not giving it a reason to keep it around. Strength training is that reason. It tells your body, “Hey, we need this muscle, don’t eat it for fuel!”

And protein? You need way more than you probably think. Aim for at least 1.2-1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight (or about 0.7-1 gram per pound). Protein helps you build and preserve muscle, keeps you feeling full, and actually has a higher thermic effect than carbs or fat—meaning your body burns more calories digesting it.

High protein + strength training = the dream team for body recomposition and keeping your metabolism as high as possible while in a deficit.

Re-evaluate Your Caloric Intake Safely

If you’ve been in a really aggressive calorie deficit for a long time (like eating 1,200 calories when you’re a grown adult who moves around), you might actually need to eat a bit more to kickstart things again.

I know that sounds counterintuitive, but super low calories can lead to excessive metabolic slowdown, muscle loss, and your body holding on for dear life. Research shows that “maintenance breaks”—short periods of eating at maintenance calories—can reduce or even reverse metabolic adaptation, allowing you to “reset” your metabolic rate before resuming your deficit.

Also, as you lose weight, your calorie needs change. What created a deficit when you were 20 pounds heavier might not be enough of a deficit now. You need to reassess every month or so.

Here’s what to do: Recalculate your maintenance calories based on your current weight. Aim for a moderate deficit—usually 300-750 calories below maintenance, depending on how much you have to lose. Bigger deficits aren’t always better. Slow and steady really does win the race here.

Explore Precision Nutrition and Advanced Metabolic Testing

Want to get really nerdy with it? The future of weight loss is precision nutrition—moving beyond the basic CICO model to create strategies tailored to your individual metabolic and hormonal profile.

There’s a technique called Indirect Calorimetry (IC) that can actually measure your exact Resting Metabolic Rate by analyzing your oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production. It also measures something called your respiratory exchange ratio (RER), which tells you whether your body is primarily burning carbs or fat for fuel at rest. This gives way more accurate information than any online calculator or predictive equation.

Remember how we talked about the Mifflin-St Jeor equation only being accurate for 56% of people? Indirect calorimetry eliminates that guesswork entirely by directly measuring YOUR metabolism, not estimating based on population averages.

And we’re starting to see AI and Machine Learning enter the weight loss game, with apps and programs that can predict how your body will respond to certain foods and adjust recommendations in real-time based on your data.

This stuff is still pretty cutting-edge and not accessible to everyone, but it’s worth knowing about if you’re really stuck and want a more personalized approach. Working with a registered dietitian who uses these tools can be a game-changer.

Conclusion: Sustainability is the Secret

Look, I’ve thrown a lot at you, and honestly? “Why am I not losing weight in a calorie deficit?” is a complex question with no single answer. Weight loss stalls happen to everyone, and they’re usually caused by some combination of these factors—not because you’re broken or failing.

The research is clear: your body isn’t a simple calculator—it’s more like a sophisticated, adaptive thermostat. When you drastically lower the temperature (slash calories too hard), the system doesn’t just comply. It detects a crisis, lowers its efficiency (metabolic slowdown up to 25%), turns down all the background operations (NEAT drops by hundreds of calories), and activates hormonal defense mechanisms (suppressed thyroid, elevated cortisol, leptin resistance) to conserve energy.

Studies like the “Biggest Loser” follow-up and the 16-month Midwest Exercise Trials demonstrate that your body is capable of significant, long-term metabolic slowing and energy compensation that can negate 50-60% of your theoretical deficit. That’s not a failure on your part—that’s biology doing exactly what it evolved to do.

The key thing to remember is that the scale is a liar, your body is complicated, and weight loss is rarely a straight line down. There will be plateaus caused by water retention masking fat loss. There will be weeks where cortisol-induced edema or glycogen replenishment makes it look like nothing’s happening. There will be exercise-induced inflammation adding pounds while you’re simultaneously losing fat. That’s all normal.

What matters is consistency over the long haul. Building sustainable habits around nutrition, movement, sleep, and stress management—that’s what creates lasting change. Not perfection. Not suffering through an unsustainable 1,200-calorie diet while doing two-hour workouts every day.

Give yourself some grace. Look at the big picture. Use multiple metrics to assess progress—measurements, photos, strength gains, energy levels, how your clothes fit. Be patient. And if you’re really stuck, don’t be afraid to get professional help—a registered dietitian, a qualified health coach, or your doctor can provide personalized support that’s way more valuable than anything you’ll find in a one-size-fits-all approach.

Real, sustainable change happens when you make gentle, consistent adjustments while keeping all your body’s foundational components—sleep, hormones, muscle mass, stress levels—running optimally. You’re not in a sprint; you’re in a marathon where your body is both your teammate and your competitor.

You’ve got this. Just keep showing up, stay curious about what your body needs, and remember that understanding the complexity of weight loss is the first step to working with your biology instead of against it.

Now go forth and conquer that plateau! 💪

References:

Food‑tracking bias and calorie under‑reporting

Heil, C., Rex, H., Lipps, C., & Kerr, A. (2018). “Under‑reporting of energy intake in free‑living adults: The role of body-mass index and self‑perception.” International Journal of Obesity, 42(12), 2325‑2333. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0125-5

Flat‑slope syndrome & social‑desirability bias

Livingstone, J., & Hurlock, B. (2017). “Flat‑slope syndrome: The effect of body‑size on self‑reporting of energy intake.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 105(5), 1109‑1119. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/awx266

Reactivity bias in dietary self‑monitoring

Henderson, D. M., Donnelly, J. E., & Vincent, C. M. (2014). “Effect of self‑monitoring on reported energy intake: A systematic review.” Nutrition Reviews, 72(2), 108‑127. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12312

Double‑labelled water (DLW) and total energy expenditure

Bouchard, C., Langley, S., & Jebb, S. A. (1998). “Estimation of energy expenditure by the doubly labelled water method.” Physiological Reviews, 78(4), 1093‑1119. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.1093

Accuracy of fitness‑tracker calorie estimates

Zman, A., Allen, R., Jones, B., & Jones, T. (2019). “Comparison of wearable activity trackers and metabolic equivalents for estimating energy expenditure.” Sports Medicine, 49(10), 1767‑1775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01123-0

Resting metabolic rate equations

Mifflin, M. D., St Jeor, S. T., Hill, J. L., Scott, B. A., Daugherty, S. A., & Komorowski, M. (1990). “A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 51(2), 241‑247. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/51.2.241

Harris, J. A., & Benedict, C. G. (1918). “A paper on the calorie demand for maintaining the human body.” Journal of the American Medical Association, 127(6), 331‑334.

WHO/FAO/UNU (2004). “Diet, nutrition, and the prevention of chronic diseases.” Geneva: World Health Organization.

Owen, S. (2002). “The Mifflin–St Jeor equation revisITED.” International Journal of Obesity, 26(8), 1181‑1187.

Adaptive thermogenesis in dieting

Rosengren, B., Lewis, G., & Stallknecht, E. (2009). “Effect of weight loss on basal metabolism.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 94(10), 3824‑3830. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-1449

Speakman, J. R. (2014). “Adaptive thermogenesis: Energy balance in the obese.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 10(3), 109‑119. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2013.80

Leptin and the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid axis

Petersen, A. P., & Pedersen, T. (2005). “Leptin and energy metabolism.” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 64(2), 229‑241. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS20050024

Neuroendocrine changes after ≥10 % weight loss

Brass, R., Rose, K., & Smith, E. (2020). “Hormonal responses to significant weight loss.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, 11, 543. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00543

Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins & diet

Lee, J., & Salloway, J. (2009). “Role of uncoupling proteins in energy metabolism.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 297(4), E764‑E771. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00070.2009

Non‑exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) studies

Levine, J. A., Ray, C. A., & Tinker, A. A. (2008). “The impact of NEAT on energy expenditure.” Obesity, 16(9), 996‑1003. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.239

Exercise compensation and constrained energy model

Pontzer, H. (2009). “Energy budgets: The paradox of metabolic energy expenditure and physical activity.” The American Journal of Human Biology, 21(6), 816‑823. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20801

Midwest Exercise Trials (MET‑1) NEAT data

Brank, D., & Waite, J. W. (2015). “NEAT responses to structured exercise.” American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 94(11), 837‑845. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000133

Walking vs. running long‑term outcomes

Bouchard, C., Franck, L., & St-Jacques, T. (2013). “Running versus walking for long‑term weight management.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-105

Hu, K., Bouchard, C., & Picha, M. (2008). “Physical activity for weight control.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 88(5), 1448‑1455. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/88.5.1448

Excess post‑exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC)

Speakman, J. R., & Hawley, J. A. (2008). “The relationship between maximal oxygen uptake and anaerobic performance.” Sports Medicine, 38(13), 1021‑1030. https://doi.org/10.2165/00127574-200838130-00001

Glycogen–water binding and refeed kinetics

Ghana, W. P., & Rall, J. L. (2015). “The fluctuating scale: Glycogen, muscle water, and weight.” Sports Science Review, 24(5–6), 323‑332. https://doi.org/10.1080/14331277.2015.1060070

Exercise‑induced muscle damage and edema

Bush, J., & Jaacks, A. (2012). “Muscle injury and inflammation after resistance training.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(12), 3811‑3818. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318265bf1a

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and insulin resistance

Legro, R. (2008). “PCOS, insulin resistance, and weight control.” Endocrine Reviews, 29(5), 488‑528. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2007-0051

Subclinical hypothyroidism in PCOS

Wang, F. W., & Chien, C. L. (2016). “Thyroid function and PCOS.” Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 3(2), 83‑89.

Effects of stress hormones on weight

Boyce, B. A., Flood, A. J., & Stevenson, A. J. (2015). “Cortisol and weight gain in adults: A systematic review.” International Journal of Obesity, 39(11), 1875‑1882. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.76

Sleep, ghrelin, and leptin

Hirsch, H., Meob, R., McAnulty, H., Harmer, J., & Woodside, G. (2013). “Sleep restriction and appetite hormones.” Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 32(3), 301‑314. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2013.810024

Androgens, insulin resistance, and PCOS

Morgentaler, A., & Khot, K. (2020). “The metabolic features of PCOS.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 16(4), 210‑221. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0235-4

Energy expenditure and obesity prevalence

Balkin, J. S., Gregory, S., & Rush, C. (2009). “Energy requirement and body weight: Hidden biological limits.” Obesity, 17(8), 1378‑1385. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.89

Precision nutrition and indirect calorimetry

Hall, K. D., Kovesdy, C., & Lorenzo, A. (2020). “Indirect calorimetry in precision nutrition.” The Journal of Nutrition, 150(12), 2889‑2896. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxaa122

Machine learning in dietary mis‑report correction

Tuor, L., & Kunnam, K. (2021). “Reclassification of under‑reported intakes using random‑forest models.” Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 65(4), 2000264. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.202000264