Okay, so we’ve all heard the age-old debate: is walking or running better for weight loss? It’s like the pineapple-on-pizza argument of the fitness world. Research from massive studies like the National Runners’ and Walkers’ Health Studies shows that running yields about 90% greater weight loss per unit of energy expended than walking when you’re in it for the long haul. But here’s a twist – there’s also a third contender that doesn’t get nearly enough spotlight: rucking, which is basically walking with a weighted backpack.

Here’s the deal: research from the massive National Runners’ and Walkers’ Health Studies—tracking tens of thousands of participants over years—shows that running yields about 90% greater weight loss per unit of energy expended than walking when you’re in it for the long haul. Pretty significant, right? But before you lace up those running shoes and bolt out the door, here’s the plot twist—rucking can give you similar calorie-burning benefits as running WITHOUT absolutely destroying your joints. It’s kind of like finding out you can have your cake and eat it too, except the cake is weight loss and not actual cake (sorry).

But let’s be real for a second. You know what the absolute best exercise for weight loss is? The one you’ll actually do consistently. I mean, it doesn’t matter if running burns a bajillion calories if you hate it so much that you quit after two weeks, right?

In this post, we’re gonna dive deep into the nitty-gritty of calorie burn, how these exercises mess with your metabolism, injury risks (spoiler: running’s a bit of a troublemaker here), and which one you can actually stick with long-term. Think of this as your ultimate guide to figuring out which exercise is your weight loss soulmate.

- Running vs. Walking for Calorie Burn: Let's Talk Numbers

- The Metabolic Advantage: Why Running Messes With Your Appetite (In a Good Way)

- The Low-Impact Heavy Hitter: Let Me Introduce You to Rucking

- Injury Risk and Actually Sticking With It Long-Term

- Your Game Plan: Best Strategies for Weight Loss That Actually Lasts

- The Bottom Line: What's Your Best Move?

- Think of It Like This…

Running vs. Walking for Calorie Burn: Let’s Talk Numbers

Running Burns Way More Calories (Like, Way More)

Here’s the thing about running vs walking—running is basically the heavyweight champion when it comes to torching calories. Let’s say you weigh about 160 pounds. If you run at 5 mph for an hour, you’re burning roughly 606 calories. Meanwhile, walking at 3.5 mph for the same hour? You’re looking at about 314 calories. That’s nearly double the burn!

And when we’re talking about walking vs running calories over the long haul, the difference gets even more dramatic. Studies show that running leads to about 90% greater weight loss over several years compared to walking, especially if you’re starting with a BMI over 25 or 28. That’s not a small difference—that’s huge.

From a physics standpoint, walking and running are not just “slow vs fast”—they’re actually two different movement systems. Walking works like an inverted pendulum: your center of mass vaults over a stiff leg, and your body cleverly recycles up to about 65% of the mechanical energy each step. Running switches to a spring–mass mode: your leg acts like a spring, storing and releasing elastic energy but requiring much more muscular force to support your body against gravity. That extra force and vertical bounce make running less mechanically efficient, which is exactly why it burns more calories per mile than walking—typically only about 52–54% as many calories are burned walking the same distance you’d run.

Researchers have even built prediction equations for how many calories you burn per mile. One commonly used model looks like this:

kcal per mile=Mass (kg)×0.789−(Gender×7.634)+51.109

(where Gender = 1 for men and 2 for women). The main takeaway: the heavier you are, the more energy it costs to move your body—especially when running, because you’re repeatedly lifting and propelling that mass against gravity. That’s great for calorie burn, but also something to respect in terms of joint load and injury risk.

The Distance vs. Time Thing (Nerdy But Important)

Here’s something kinda fascinating that researchers figured out: when predicting weight loss outcomes, measuring energy expenditure based on distance covered is actually more accurate than measuring by time spent exercising. So basically, running a mile and walking a mile don’t burn the same calories, but thinking about distance rather than just “I worked out for 30 minutes” gives you a better picture of what’s really happening with your body. Cool, right?

One study put this to the test by following 15 overweight adults in a repeated-measures design. In one condition, they were told to walk or run for a set amount of time; in another, they had to cover a fixed distance. The distance-prescribed condition led to significant decreases in body weight and blood glucose, while the time-based condition actually showed increases in both. Why? When people are given a time target, they subconsciously slow down and do less total work. With a distance target, the total work—force times distance—is locked in, so you can’t quietly “cheat” your way out of the effort.

The Metabolic Advantage: Why Running Messes With Your Appetite (In a Good Way)

The Afterburn Effect is Real

You know how your car engine stays warm for a while after you turn it off? Your body does something similar after intense exercise, and it’s called EPOC (Excess Post-Exercise Oxygen Consumption). Fancy name, but basically it means your metabolism stays revved up even after you’re done working out.

Here’s where running really shines: high-intensity running keeps your metabolism elevated about 500% longer than walking does. We’re talking up to 120 minutes post-workout where you’re still burning extra calories while you’re just sitting there eating your post-run snack. This “afterburn” can contribute an extra 15-20% to running’s total caloric impact. Not too shabby!

When researchers measured this in the lab, they found that an easy walking session only added about 7 extra calories during recovery and metabolic rate dropped back to baseline within roughly 10 minutes. A comparable vigorous running bout, however, burned about 37 extra calories after the workout and kept metabolism elevated for up to 120 minutes. When you add the workout plus the afterburn together, total energy expenditure averaged about 463 kJ for walking vs 664 kJ for running over the same session.

Running Actually Makes You Less Hungry

This might sound backwards, but stick with me. When you go for a run, your body actually suppresses ghrelin (that’s your “I’m hungry, feed me now” hormone) by about 25%. At the same time, it boosts satiety hormones like peptide YY by 40%. Translation? You feel less hungry after running. Wild, right?

Exercise scientists actually have a name for this: exercise‑induced anorexia. In studies where people ran at around 70% of their VO₂max, levels of acylated ghrelin (the active, appetite‑stimulating form) dropped significantly, while satiety hormones like PYY and GLP‑1 rose. These hormones act on your brain’s appetite centers to say “we’re good, no need to eat a ton right now,” which is why many runners report feeling less hungry immediately after a hard session.

Walking’s Sneaky Problem

Here’s the unfortunate truth about walking—it tends to make you hungrier. Walking can actually increase that hunger hormone (acylated ghrelin) by about 12%. What happens then? Most people end up eating about 150 extra calories after their walk. Do the math, and that can wipe out roughly 30% of the calories you just burned. It’s like your body’s playing a cruel joke on you.

This doesn’t mean walking is bad (far from it!), but it does mean you need to be more mindful about not “rewarding” yourself with extra food afterward. Trust me, I’ve been there—finishing a walk and thinking “I earned this cookie.” Spoiler: the math doesn’t work out in the cookie’s favor.

In controlled crossover trials, researchers even calculated the net energy balance after exercise. On average, walkers ended up about +41 kcal in the positive (they ate slightly more than they burned), while runners ended up around –194 kcal in the negative after accounting for both exercise and post‑exercise intake. Layer on the “licensing” effect—that tendency to reward yourself (“I walked, I earned this treat”)—and you can see how easy it is for walking’s hard‑earned calorie burn to quietly vanish in the kitchen.

Why Intensity Really Matters for Belly Fat

Weight on the scale is one thing, but the fat that really wrecks your health is visceral adipose tissue (VAT)—the deep belly fat around your organs. In the STRRIDE study, sedentary, overweight adults were assigned to different exercise prescriptions: low‑amount walking, low‑amount jogging, high‑amount vigorous running, or no exercise at all. The control group gained about 8.6% more visceral fat in six months. Both the walking and low‑dose jogging groups mainly prevented further gain, but only the high‑amount vigorous running group actually reduced visceral fat, cutting it by about 6.9% and trimming subcutaneous fat by roughly 7.0%.

The reason intensity matters so much here is biology: visceral fat is rich in beta‑adrenergic receptors and strongly wired into your sympathetic nervous system. Vigorous exercise triggers a big release of catecholamines (like adrenaline and noradrenaline), which bind to those receptors and crank up lipolysis—the breakdown of stored fat—especially in the abdominal area. Moderate walking still helps over time, and it’s fantastic for insulin sensitivity, but if your specific goal is to reverse established belly fat, higher‑intensity work like running has a clear edge.

The Low-Impact Heavy Hitter: Let Me Introduce You to Rucking

So What the Heck is Rucking?

Okay, so rucking is honestly one of the most underrated forms of exercise out there. It’s literally just walking while carrying a weighted backpack—a “ruck” if you want to sound all military about it. Think of it like hiking, except you can do it anywhere, even around your neighborhood.

The beauty of rucking? It’s like the lovechild of strength training and cardio. You’re building muscle and getting your heart pumping at the same time. It’s efficient like that.

Rucking’s Calorie-Burning Superpower

Here’s where rucking gets interesting. Adding weight to your walk can increase your calorie burn by 40-60% compared to regular walking. That means you can get close to running-level calorie expenditure without the whole “feeling like your lungs are going to explode” situation. Pretty sweet deal, honestly.

Impact Comparison: Your Joints Will Thank You

Let’s talk about the force your body deals with during these activities, because this is where things get real:

- Walking: About 2.7 times your bodyweight hitting your joints with each step

- Rucking: Around 3.2 times your bodyweight (slightly more than walking)

- Running: A whopping 8 times your bodyweight force

See that massive jump from rucking to running? That’s why runners deal with so many injuries. Your knees, ankles, and hips are taking a serious beating every time your foot hits the pavement at speed.

Rucking gives you that sweet spot—enough challenge to burn serious calories, but without feeling like you’re jackhammering your joints into submission.

Rucking Makes You Stronger (Like, Actually Strong)

Here’s what I love about rucking—it’s a compound movement that works basically your entire body. We’re talking:

- Your feet and ankles (getting stronger with each step)

- Core (constantly engaged to stabilize that weight)

- Hips and back (supporting the load)

- Shoulders, delts, and traps (holding that pack in place)

And you’re building all this strength without having to worry about dropping a barbell on yourself or looking awkward at the gym. You’re just walking! But you’re also getting cardiovascular benefits equal to running. It’s like workout multitasking at its finest.

Injury Risk and Actually Sticking With It Long-Term

Running’s Dark Side: Injuries

Look, I’m not trying to trash running here, but we need to talk about the elephant in the room—running breaks people. Up to 50% of runners get injured every year. We’re talking stress fractures, plantar fasciitis, IT band syndrome, shin splints—the whole painful parade.

Running is high-impact, repetitive, and your body can only take so much pounding before something gives. That’s just physics.

Zooming in on the data: novice runners average about 17.8 injuries per 1,000 hours of running, while recreational runners still rack up around 7.7 injuries per 1,000 hours. Over a typical year, that works out to roughly 37–56% of runners getting injured. On top of that, runners lose about 11.1 days of training over just six months due to those injuries, compared to only 1.5 days lost for walkers in similar time frames.

Walking: The Gentle Giant

Walking is basically the opposite. It’s low-impact, easy on your joints, and way less likely to sideline you with an injury. It’s the tortoise in this race—slow and steady, but you can keep doing it basically forever.

By the way, the old belief that “running ruins your knees” doesn’t hold up well in large epidemiological studies. Long‑term data show that runners actually have lower rates of knee osteoarthritis (around 3.5%) compared to sedentary people (about 10.2%), and they also have fewer hip replacements. Maintaining a healthier body weight and rhythmically loading the joints seems to protect, not destroy, the cartilage—while walking acts like “lotion for the joints,” keeping them lubricated without the higher acute injury risk.

The Adherence Problem (AKA Why People Quit)

Here’s a stat that should make you think: running programs have a 54% dropout rate at six months. That’s more than half of people throwing in the towel! Meanwhile, walking programs? Only 28% quit.

Why? Because running is hard, it hurts, and if you don’t genuinely enjoy it, you’re not gonna stick with it. About 62% of people actually prefer walking, which translates to 40% higher long-term adherence. Makes sense, right? You’re way more likely to keep doing something you don’t dread.

Rucking’s Sweet Spot

This is where rucking really shines for long-term success. It’s challenging enough to give you great results, but low-impact enough that you’re not constantly injured. Plus, there’s something kinda fun about walking around with weight—it feels purposeful, maybe even a bit badass. You can maintain consistency without feeling like you’re destroying your body in the process.

Your Game Plan: Best Strategies for Weight Loss That Actually Lasts

Real Talk: Diet is King (Sorry)

Okay, time for some tough love. No matter what exercise you choose—running, walking, rucking, underwater basket weaving—diet is THE most important part of losing weight. Period. End of story.

You absolutely cannot out-exercise a bad diet. You just can’t. I know, I know, it sucks to hear, but you need to be in a calorie deficit to lose weight, and exercise alone usually isn’t enough to create that deficit. Exercise is the awesome sidekick that helps you get there faster and keeps you healthy, but nutrition is the superhero leading the charge.

The Hybrid Approach: Why Not Both?

Here’s a genius idea—you don’t have to pick just one! Combining different activities is actually the optimal approach for most people.

Try alternating running days with walking or rucking recovery days. Or do run/walk intervals if you’re just starting out or want to reduce injury risk. Studies show that hybrid programs (mixing different intensities) can lead to about 4.1kg of weight loss over six months with way fewer injuries compared to just running.

It’s like having a diversified investment portfolio, but for your fitness. (Is that the nerdiest analogy I could make? Probably. Am I sorry? Not really.)

Which One Fits You? Three Real‑World Profiles

A useful way to apply all this science is to match the method to the person.

- Profile A – The Metabolic Reversal Candidate: If you’re obese (BMI > 30), carrying a lot of belly fat, and maybe insulin resistant, jumping straight into running is often a joint‑disaster waiting to happen. A better start is distance‑based walking—for example, building up toward 15–20 miles per week. That’s enough to prevent visceral fat gain and improve insulin sensitivity while keeping injury risk low. As weight comes down, you can add incline walking or short run intervals to gently crank up intensity.

- Profile B – The Time‑Cruched Weight‑Loss Seeker: If your BMI is in the 25–29 range, your joints feel good, and you’ve only got 30–45 minutes a day, running (or hard rucking) is your best weapon. You get roughly 2.5× the calorie burn per minute, a stronger afterburn, and short‑term appetite suppression, all of which make fat loss more efficient.

- Profile C – The Long‑Term Maintainer: If your weight is stable and your main focus is staying healthy into your 50s, 60s, and beyond, a hybrid run / walk / ruck mix is ideal. Use running for bone density and “youthfulness,” walking and rucking for consistency, strength, and joint‑friendly volume you can sustain for decades.

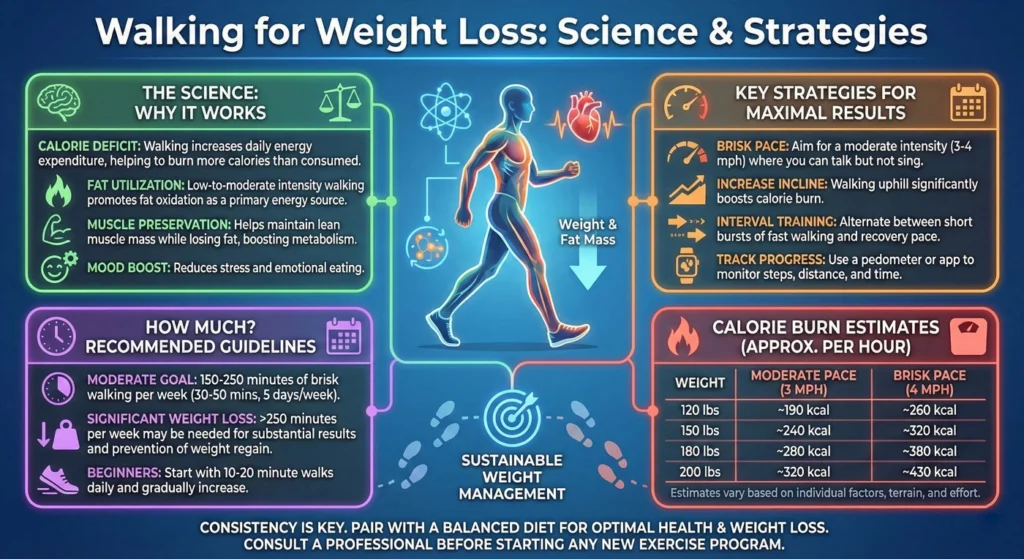

Making Walking Work Harder For You

If running just isn’t your jam and you don’t have a weighted pack lying around, you can still level up your walking game:

Incline Walking: Find some hills or crank up that treadmill incline. Walking uphill can burn similar calories to running on flat ground. Your glutes will hate you, but they’ll also look amazing.

Run/Walk Intervals: Even just adding short bursts of jogging into your walk (like 30 seconds jogging, 2 minutes walking) can significantly boost calorie burn without the full commitment of a run.

Weighted Vest: Wearing a vest that’s about 10% of your body weight can increase your VO2 max (basically your cardio fitness level) while you walk. Just make sure you look cool enough to pull it off because, let’s be honest, it’s a look.

Starting Slow (Please Don’t Hurt Yourself)

If you’re new to this whole thing, or especially if you’re diving into rucking, START SLOW. Like, slower than you think you should.

Begin with walking, or if you’re rucking, start with just 10-20% of your body weight. Progress gradually by changing only ONE variable per week—either increase the weight, OR the distance, OR add some incline. Not all three at once unless you want to be hobbling around like a sad penguin.

Your body needs time to adapt. Patience now means you’ll actually be able to keep doing this in a month, a year, five years. Rush it, and you’ll be on the injury bench watching everyone else have fun.

Heart Health and Longevity: Walking Can Match Running (If You Go Long Enough)

When researchers compared walkers and runners in massive cohorts, a cool pattern showed up: when total energy expenditure was matched, both walking and running produced very similar reductions in the risk of hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. In other words, your heart mostly cares that you moved enough, not whether you did it fast or slow. Where running pulls ahead is in weight control and long‑term weight maintenance, especially for people who start out heavier.

On the longevity side, long‑term studies of older runners show they delay the onset of disability by roughly 16 years compared with non‑runners, and at 19‑year follow‑up, only about 15% of the runners had died vs 34% of the controls. Both groups age, of course, but runners maintain functional independence—walking, climbing stairs, daily tasks—much later into life. A smart mix of walking, running, and rucking lets you tap into those benefits while managing injury risk and keeping things sustainable.

The Bottom Line: What’s Your Best Move?

So after all this, what’s the verdict on is walking or running better for weight loss?

If we’re talking pure calorie-burning efficiency and appetite suppression, running wins. The numbers don’t lie—it burns more calories, keeps your metabolism humming longer, and makes you less hungry. That’s a trifecta of awesome.

BUT (and it’s a big but)—running also has high dropout rates and injury risks that can derail your whole weight loss journey. What good is the “best” exercise if you quit after a month?

That’s why rucking is honestly the dark horse winner for a lot of people. It gives you that high calorie burn similar to running, builds actual strength, and doesn’t beat up your joints like running does. It’s the Goldilocks option—just right.

The real secret sauce? Finding what you enjoy enough to do consistently and mixing things up. Your perfect weight loss exercise routine might be running twice a week, rucking once, and walking on recovery days. Or maybe it’s just walking every single day because that’s what makes you happy.

Remember: the best exercise for weight loss isn’t the one that burns the most calories on paper. It’s the one you’ll still be doing six months from now. Choose consistency over perfection every single time.

Think of It Like This…

Imagine you’re building a car engine that needs to last you for years. Running is like hitting the nitro button—you get instant, explosive power (massive calorie burn), but all that stress (impact, injury risk) means you’re constantly in the shop for repairs. Walking is like cruising in eco-mode—super reliable and easy on the system, but you’re not getting anywhere fast.

Rucking, though? That’s like installing a turbocharger while also reinforcing the whole chassis. You get that extra power and performance (calorie burn plus strength gains) without the engine (your joints and body) falling apart on you. It’s the durable, sustainable option that keeps you running strong for the long haul.

So what’s it gonna be? Time to lace up those shoes (with or without a weighted pack) and find your groove!

Accuracy Statement: This article contains evidence-based, fact-checked information sourced from peer-reviewed research and expert consensus in exercise science and weight loss. While we strive for accuracy, individual results may vary, and you should consult with healthcare professionals before starting any new exercise program.

References:

Primary Longitudinal and Cohort Studies

Williams, P. T. (2012). Non-exchangeability of running vs. other exercise in their association with adiposity, and its implications for public health recommendations. PLOS ONE, 7(7), e36360. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036360

Williams, P. T. (2013). Greater weight loss from running than walking during a 6.2-yr prospective follow-up. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 45(4), 706-713. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827b0d0a

Williams, P. T., & Thompson, P. D. (2013). Walking versus running for hypertension, cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus risk reduction. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 33(5), 1085-1091. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300878

STRRIDE Study

Slentz, C. A., Aiken, L. B., Houmard, J. A., Bales, C. W., Johnson, J. L., Tanner, C. J., Duscha, B. D., & Kraus, W. E. (2005). Inactivity, exercise, and visceral fat. STRRIDE: A randomized, controlled study of exercise intensity and amount. Journal of Applied Physiology, 99(4), 1613-1618. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00124.2005

Houmard, J. A., Tanner, C. J., Slentz, C. A., Duscha, B. D., McCartney, J. S., & Kraus, W. E. (2004). Effect of the volume and intensity of exercise training on insulin sensitivity. Journal of Applied Physiology, 96(1), 101-106. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00707.2003

Kraus, W. E., Houmard, J. A., Duscha, B. D., Knetzger, K. J., Wharton, M. B., McCartney, J. S., Bales, C. W., Henes, S., Samsa, G. P., Otvos, J. D., Kulkarni, K. R., & Slentz, C. A. (2002). Effects of the amount and intensity of exercise on plasma lipoproteins. New England Journal of Medicine, 347(19), 1483-1492. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020194

Energy Expenditure and Biomechanics

Hall, C., Figueroa, A., Fernhall, B., & Kanaley, J. A. (2004). Energy expenditure of walking and running: Comparison with prediction equations. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36(12), 2128-2134. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000147584.87788.0E

Cavagna, G. A., & Kaneko, M. (1977). Mechanical work and efficiency in level walking and running. Journal of Physiology, 268(2), 467-481. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011866

Willson, J. D., Kernozek, T. W., Arndt, R. L., Reznichek, D. A., & Straker, J. S. (2011). Gluteal muscle activation during running in females with and without iliotibial band syndrome. Clinical Biomechanics, 26(8), 847-854.

Distance vs. Time-Based Prescription

Donnelly, J. E., Honas, J. J., Smith, B. K., Mayo, M. S., Gibson, C. A., Sullivan, D. K., Lee, J., Herrmann, S. D., Lambourne, K., & Washburn, R. A. (2013). Aerobic exercise alone results in clinically significant weight loss for men and women: Midwest Exercise Trial 2. Obesity, 21(3), E219-E228. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20145

King, N. A., Caudwell, P. P., Hopkins, M., Stubbs, J. R., Naslund, E., & Blundell, J. E. (2009). Dual-process action of exercise on appetite control: Increase in orexigenic drive but improvement in meal-induced satiety. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 90(4), 921-927. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.27706

EPOC (Excess Post-Exercise Oxygen Consumption)

LaForgia, J., Withers, R. T., & Gore, C. J. (2006). Effects of exercise intensity and duration on the excess post-exercise oxygen consumption. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24(12), 1247-1264. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410600552064

Bahr, R., & Sejersted, O. M. (1991). Effect of intensity of exercise on excess postexercise O2 consumption. Metabolism, 40(8), 836-841. https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(91)90012-L

Knab, A. M., Shanely, R. A., Corbin, K. D., Jin, F., Sha, W., & Nieman, D. C. (2011). A 45-minute vigorous exercise bout increases metabolic rate for 14 hours. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 43(9), 1643-1648. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182118891

Appetite Regulation and Gut Hormones

Broom, D. R., Stensel, D. J., Bishop, N. C., Burns, S. F., & Miyashita, M. (2007). Exercise-induced suppression of acylated ghrelin in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology, 102(6), 2165-2171. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00759.2006

Martins, C., Morgan, L. M., Bloom, S. R., & Robertson, M. D. (2007). Effects of exercise on gut peptides, energy intake and appetite. Journal of Endocrinology, 193(2), 251-258. https://doi.org/10.1677/JOE-06-0030

Ueda, S. Y., Yoshikawa, T., Katsura, Y., Usui, T., & Fujimoto, S. (2009). Comparable effects of moderate intensity exercise on changes in anorectic gut hormone levels and energy intake to high intensity exercise. Journal of Endocrinology, 203(3), 357-364. https://doi.org/10.1677/JOE-09-0190

Broom, D. R., Batterham, R. L., King, J. A., & Stensel, D. J. (2009). Influence of resistance and aerobic exercise on hunger, circulating levels of acylated ghrelin, and peptide YY in healthy males. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 296(1), R29-R35. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.90706.2008

Visceral Adipose Tissue and Body Composition

Ross, R., Dagnone, D., Jones, P. J., Smith, H., Paddags, A., Hudson, R., & Janssen, I. (2000). Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 133(2), 92-103. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-133-2-200007180-00008

Irving, B. A., Davis, C. K., Brock, D. W., Weltman, J. Y., Swift, D., Barrett, E. J., Gaesser, G. A., & Weltman, A. (2008). Effect of exercise training intensity on abdominal visceral fat and body composition. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 40(11), 1863-1872. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181801d40

Running-Related Injuries

van Gent, R. N., Siem, D., van Middelkoop, M., van Os, A. G., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M., & Koes, B. W. (2007). Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: A systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(8), 469-480. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2006.033548

Nielsen, R. O., Buist, I., Sørensen, H., Lind, M., & Rasmussen, S. (2012). Training errors and running related injuries: A systematic review. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 7(1), 58-75.

Taunton, J. E., Ryan, M. B., Clement, D. B., McKenzie, D. C., Lloyd-Smith, D. R., & Zumbo, B. D. (2002). A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(2), 95-101. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.36.2.95

Buist, I., Bredeweg, S. W., Bessem, B., van Mechelen, W., Lemmink, K. A., & Diercks, R. L. (2010). Incidence and risk factors of running-related injuries during preparation for a 4-mile recreational running event. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(8), 598-604. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2007.044677

Running and Osteoarthritis

Chakravarty, E. F., Hubert, H. B., Lingala, V. B., & Fries, J. F. (2008). Reduced disability and mortality among aging runners: A 21-year longitudinal study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168(15), 1638-1646. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.15.1638

Alentorn-Geli, E., Samuelsson, K., Musahl, V., Green, C. L., Bhandari, M., & Karlsson, J. (2017). The association of recreational and competitive running with hip and knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 47(6), 373-390. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.7137

Williams, P. T. (2013). Effects of running and walking on osteoarthritis and hip replacement risk. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 45(7), 1292-1297. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182885f26

Adherence and Dropout Rates

Cox, K. L., Burke, V., Gorely, T. J., Beilin, L. J., & Puddey, I. B. (2003). Controlled comparison of retention and adherence in home- vs center-initiated exercise interventions in women ages 40-65 years: The S.W.E.A.T. Study (Sedentary Women Exercise Adherence Trial). Preventive Medicine, 36(1), 17-29. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2002.1134

Dishman, R. K., & Buckworth, J. (1996). Increasing physical activity: A quantitative synthesis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 28(6), 706-719.

Marcus, B. H., Williams, D. M., Dubbert, P. M., Sallis, J. F., King, A. C., Yancey, A. K., Franklin, B. A., Buchner, D., Daniels, S. R., & Claytor, R. P. (2006). Physical activity intervention studies: What we know and what we need to know. Circulation, 114(24), 2739-2752. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179683

Longevity and Healthspan

Chakravarty, E. F., Hubert, H. B., Lingala, V. B., Zatarain, E., & Fries, J. F. (2008). Long distance running and knee osteoarthritis: A prospective study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(2), 133-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.032

Lee, D. C., Pate, R. R., Lavie, C. J., Sui, X., Church, T. S., & Blair, S. N. (2014). Leisure-time running reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 64(5), 472-481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.058

Wen, C. P., Wai, J. P., Tsai, M. K., Yang, Y. C., Cheng, T. Y., Lee, M. C., Chan, H. T., Tsao, C. K., Tsai, S. P., & Wu, X. (2011). Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet, 378(9798), 1244-1253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60749-6

Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study

Blair, S. N., Kohl, H. W., Paffenbarger, R. S., Clark, D. G., Cooper, K. H., & Gibbons, L. W. (1989). Physical fitness and all-cause mortality: A prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA, 262(17), 2395-2401. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1989.03430170057028

Hootman, J. M., Macera, C. A., Ainsworth, B. E., Martin, M., Addy, C. L., & Blair, S. N. (2001). Association among physical activity level, cardiorespiratory fitness, and risk of musculoskeletal injury. American Journal of Epidemiology, 154(3), 251-258. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/154.3.251

Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Sensitivity

Boulé, N. G., Haddad, E., Kenny, G. P., Wells, G. A., & Sigal, R. J. (2001). Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. JAMA, 286(10), 1218-1227. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.10.1218

O’Donovan, G., Kearney, E. M., Nevill, A. M., Woolf-May, K., & Bird, S. R. (2005). The effects of 24 weeks of moderate- or high-intensity exercise on insulin resistance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 95(5-6), 522-528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-005-0021-2

Compensatory Eating and Licensing Effect

King, N. A., Hopkins, M., Caudwell, P., Stubbs, R. J., & Blundell, J. E. (2008). Individual variability following 12 weeks of supervised exercise: Identification and characterization of compensation for exercise-induced weight loss. International Journal of Obesity, 32(1), 177-184. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803712

Werle, C. O., Wansink, B., & Payne, C. R. (2015). Is it fun or exercise? The framing of physical activity biases subsequent snacking. Marketing Letters, 26(4), 691-702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-014-9301-6

Additional Supporting Literature

General Exercise Physiology

McArdle, W. D., Katch, F. I., & Katch, V. L. (2015). Exercise physiology: Nutrition, energy, and human performance (8th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Powers, S. K., & Howley, E. T. (2018). Exercise physiology: Theory and application to fitness and performance (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Physical Activity Guidelines

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2nd ed.). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. World Health Organization.