So, you’ve probably heard your gym buddy or that one fitness influencer on Instagram talking about “counting macros,” right? It’s basically everywhere these days—athletes swear by it, health coaches won’t shut up about it, and honestly, it’s become the conversation starter at any wellness-focused brunch. But here’s the thing: it’s not just another diet fad that’ll disappear next month.

Let me break it down for you. Macros for weight loss is all about understanding the big picture of what you’re putting in your body. We’re talking about macronutrients—protein, carbs, and fat—which are basically the three main nutrients that keep your body running like a well-oiled machine. Instead of just obsessing over that calorie number on the back of your protein bar, tracking macros helps you make sure those calories are actually coming from the right places.

And here’s why I think counting macros beats the old-school calorie counting game: it’s not just about how much you eat, but what you eat. You could technically hit your calorie goal by eating nothing but gummy bears (don’t try this at home), but your body would be screaming for actual nutrients. Counting macros for weight loss helps you nail that sweet spot where you’re eating enough protein to keep your muscles happy, enough carbs to fuel your day, and enough fat to keep you satisfied. It’s like giving your body a balanced meal plan instead of just throwing random food at it and hoping for the best.

- What Are Macronutrients? Defining the "Big Three"

- Step-by-Step Guide: How to Calculate Your Personal Macro Targets

- Real-World Application: Clinical Case Studies

- Optimal Macro Ratios for Specific Health and Fitness Goals

- Flexible Dieting (IIFYM): Achieving Sustainable Adherence

- Mastering the Art of Macro Tracking: Tips for Accuracy and Consistency

- Adjusting Macros for Health Conditions and Age

- Conclusion: Sustainability is the Key to Long-Term Success

What Are Macronutrients? Defining the “Big Three”

Alright, let’s get into the nitty-gritty. What exactly are these mysterious macronutrients everyone’s obsessing over?

Protein: The Building Block

Think of protein as your body’s construction crew. Seriously, it’s out here building and repairing everything—your muscles after that brutal leg day, your hair, your nails, even the enzymes that help you digest that pizza you had last night. If you’re trying to lose weight, protein is your best friend because it helps you hang onto that hard-earned muscle mass while you’re in a calorie deficit.

Here’s a fun fact: 1 gram of protein gives you 4 calories. Not too shabby, right?

Where can you find this magical macro? Pretty much anywhere you look—chicken, fish, beef, eggs, Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, beans, lentils, tofu, nuts, and seeds. My personal go-to? A good old-fashioned omelet with some cheese. Can’t beat it.

Carbohydrates: The Primary Fuel Source

Okay, let’s talk about carbs—the macro that gets way too much hate. Carbs are literally your body’s favorite energy source. Your muscles love them, your brain runs on them (hello, glucose!), and your central nervous system basically needs them to function. When you eat carbs, your body breaks them down into glucose, which is like premium fuel for your brain and body.

Just like protein, carbs clock in at 4 calories per gram.

You’ll find carbs in stuff like rice, pasta, bread, oats, potatoes, sweet potatoes, beans, fruits, and even milk. Yeah, milk has carbs—bet you didn’t see that coming. How to calculate macros for weight loss often involves finding the right carb balance for your activity level and personal preference.

Fats: Essential for Health and Satiety

Now, fats might sound scary (thanks, 1990s diet culture), but they’re actually super important. We’re talking about absorbing vitamins, making hormones, keeping your body temperature regulated, and protecting your organs. Plus, fats slow down digestion, which means you stay fuller longer and don’t get those dramatic blood sugar spikes and crashes.

Here’s the kicker though: fat is calorie-dense. One gram packs 9 calories, which is why a handful of nuts can rack up the calories faster than you’d think.

Good fat sources include avocados (yes, your avocado toast is legit), olive oil, butter, fatty fish like salmon, cheese, nuts, seeds, and coconut oil. Just remember to measure these bad boys out because it’s ridiculously easy to go overboard.

The Fourth Macro: Alcohol

Plot twist! There’s actually a fourth macro, and it’s alcohol. Now, before you get too excited, let me tell you that alcohol provides 7 calories per gram but gives you exactly zero nutritional value. No vitamins, no minerals, nada. It’s basically empty calories that can seriously mess with your weight loss goals. Plus, let’s be real—those drunk munchies aren’t helping anyone’s macro targets.

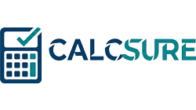

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Calculate Your Personal Macro Targets

Alright, this is where things get practical. Let me walk you through how to calculate macros for weight loss step by step. Don’t worry, it’s way easier than it sounds.

Step 1: Determine Your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR or REE)

Your BMR (or REE—they’re basically the same thing) is the number of calories your body burns just by existing. Like, if you literally laid in bed all day doing nothing, this is what you’d burn just keeping your heart beating, your brain thinking, and your lungs breathing.

Here’s the formula most pros use—it’s called the Mifflin-St. Jeor equation:

For guys: 10 x weight (kg) + 6.25 x height (cm) – 5 x age + 5 = BMR

For women: 10 x weight (kg) + 6.25 x height (cm) – 5 x age – 161 = BMR

Yeah, I know—the ladies get the short end of the stick with that -161. Life’s not fair, folks.

Step 2: Calculate Your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE)

Your TDEE is where the magic happens. This is your BMR plus all the calories you burn through actual movement—going to work, hitting the gym, chasing your dog around the park, all of it.

To figure this out, you multiply your BMR by an activity factor:

- Sedentary (x 1.2): Basically if you’re glued to your desk all day with minimal exercise

- Lightly active (x 1.375): You move around a bit, maybe hit the gym 1-3 times a week

- Moderately active (x 1.55): Working out most days, staying pretty active

- Very active (x 1.725): Hard workouts every single day

- Extra active (x 1.9): You’re basically a professional athlete training twice a day

Be honest with yourself here. Most of us are way more sedentary than we think. Using a macro calculator for weight loss can help simplify this process too.

Step 3: Adjust TDEE Based on Your Goal

Now here’s where you customize things based on what you’re actually trying to do:

Want to lose weight? You need a calorie deficit. Cut your TDEE by about 15-20%, or roughly 200-400 calories per day. This creates that sweet spot where you’re losing fat but not feeling like you’re starving.

Want to gain muscle? Time for a calorie surplus. Add 200-400 (or more) calories to your TDEE. Just remember, you can’t build something from nothing—your body needs extra fuel to build muscle.

Happy where you are? Just eat at your TDEE and call it a day. Maintenance mode engaged.

Real-World Application: Clinical Case Studies

To show you how all this theory translates into actual practice, let me walk you through some detailed case studies that demonstrate how different people need completely different approaches to macro counting. These examples come from clinical research and show the kind of precision that nutrition professionals use when calculating macros for weight loss.

Case Study 1: Sarah – The Sedentary Office Worker

Profile: 45-year-old woman, 5’5″ (165 cm), 165 lbs (75 kg)

Lifestyle: Desk job, walks the dog for 20 minutes daily, no gym membership

Goal: Lose 22 pounds (10 kg)

The Calculation Process:

Using the Mifflin-St. Jeor equation:

BMR = (10 × 75) + (6.25 × 165) – (5 × 45) – 161 = 1,396 calories/day

For her TDEE, given her truly sedentary lifestyle, we use the 1.2 multiplier:

TDEE = 1,396 × 1.2 = 1,675 calories/day

Here’s where it gets tricky. A standard 500-calorie deficit would put Sarah at only 1,175 calories, which is below the recommended minimum for women. Instead, we create a more moderate 325-calorie deficit and suggest she add 30 minutes of daily walking to increase her energy expenditure.

Final Target: 1,350 calories daily

Macro Breakdown:

- Protein: 135g (40% of calories) – This high protein percentage helps with satiety on lower calories

- Fat: 45g (30% of calories) – Higher fat for hormonal health and satiety

- Carbs: 100g (30% of calories) – Lower carbs due to sedentary lifestyle

Key Insight: Sarah’s plan prioritizes protein heavily because when you’re eating fewer calories, every gram needs to work harder to keep you satisfied and preserve muscle mass.

Case Study 2: Linda – The Metabolically Resistant Client

Profile: 55-year-old woman, 5’3″ (160 cm), 220 lbs (100 kg), BMI 39

Lifestyle: Sedentary with a history of yo-yo dieting

Goal: Sustainable weight loss without triggering restrict-overeat cycles

The Calculation Process:

BMR = (10 × 100) + (6.25 × 160) – (5 × 55) – 161 = 1,564 calories/day

TDEE = 1,564 × 1.2 = 1,877 calories/day

Given Linda’s history of extreme dieting, we use a conservative 400-calorie deficit (about 20%) to prevent the psychological stress that leads to diet failure.

Final Target: 1,475 calories daily

Here’s a crucial adjustment: Using Linda’s current weight (220 lbs) for protein calculations would give us 200g of protein, which is nearly impossible to eat on 1,475 calories. Instead, we base her protein needs on her goal weight of about 155 lbs.

Macro Breakdown:

- Protein: 130g (35% of calories)

- Fat: 57g (35% of calories) – Higher fat often helps with satiety in insulin-resistant individuals

- Carbs: 110g (30% of calories)

Key Insight: For people with metabolic resistance or yo-yo diet history, sustainability trumps aggressive deficits every single time.

Case Study 3: Mark – The Active Body Recomposition

Profile: 30-year-old man, 5’10” (178 cm), 180 lbs (82 kg)

Lifestyle: Desk job but heavy lifting 4x/week

Goal: Lose fat while gaining muscle (“recomposition”)

The Calculation Process:

BMR = (10 × 82) + (6.25 × 178) – (5 × 30) + 5 = 1,788 calories/day

For Mark’s activity level, we’re looking at somewhere between “Lightly Active” (1.375) and “Moderately Active” (1.55). We split the difference at 1.45 to be safe.

TDEE = 1,788 × 1.45 = 2,592 calories/day

Since Mark wants to build muscle while losing fat, we use a very small deficit of only 250 calories (about 10%) to ensure he has enough energy for muscle growth.

Final Target: 2,340 calories daily

Macro Breakdown:

- Protein: 180g (31% of calories) – High protein for muscle synthesis

- Fat: 65g (25% of calories) – Moderate fat

- Carbs: 260g (44% of calories) – High carbs to fuel intense training

Key Insight: Mark gets to eat significantly more carbohydrates because his body actually uses them for high-intensity training. This is functional fuel, not just empty calories.

What These Case Studies Teach Us

Notice how different these three approaches are, even though they all use the same basic formulas? This is why cookie-cutter macro calculators often fail. Sarah needs high protein and moderate everything else to manage hunger on low calories. Linda needs a conservative approach that prioritizes adherence over aggression. Mark gets to eat more carbs because his body actually uses them for fuel.

The math gives us the framework, but the individual circumstances determine the actual prescription. Your age, activity level, diet history, and metabolic health all influence how these numbers get applied in real life.

Optimal Macro Ratios for Specific Health and Fitness Goals

Here’s the fun part—not everyone needs the same macro split. Shocking, I know. What works for your CrossFit-obsessed coworker might be totally different from what you need.

General Health and Maintenance (AMDR)

The nutrition nerds call these the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDRs). Basically, these are the ranges recommended for most people to reduce the risk of chronic diseases:

- Carbs: 45-65% of your total calories

- Protein: 10-35% of total calories (though aiming for at least 1.2 g/kg is smart)

- Fats: 20-35% of total calories (and try to keep saturated fat under 10%)

Macros for Weight Loss and Fat Loss

Okay, listen up because this is crucial. When you’re trying to drop fat, protein is king. I’m not kidding. Higher protein intake keeps you fuller longer, uses more energy just to digest (yeah, eating protein actually burns calories!), and helps you keep your muscle while losing fat. Nobody wants to look like a deflated balloon after losing weight.

Here are some solid splits for weight loss:

Aggressive Fat Loss: Protein 25-35%, Carbs 35-50%, Fats 20-30%

General Weight Loss: Protein 20-25%, Carbs 45-55%, Fats 20-30%

Pro tip: Aim for that 30% protein range if you’re in a significant calorie deficit. Or shoot for about 1.8 grams per kilogram of body weight. Your muscles will thank you.

Macros for Muscle Gain (Bulking)

Trying to build some serious muscle? You need to be eating in a surplus and getting enough protein. We’re talking 1.6 to 2.2 grams per kilogram of body weight. That might only look like 20% of your calories, but the absolute amount matters more than the percentage.

A good starting point: Protein 25-35%, Carbs 40-55%, Fats 20-30%

The key here is consistency and eating a small surplus (300-500 extra calories daily). Don’t go overboard and eat everything in sight—you’ll just get fat, not jacked.

Specialized Macro Splits (Keto & Low-Carb)

Some people swear by going low-carb, and honestly, it works for some folks.

Low-Carb, High-Protein: This is great for satiety. You’re looking at something like Protein 40%, Carbs 20%, Fats 40%. The high protein and fat combo keeps you super full, which often leads to naturally eating fewer calories overall.

Keto-Friendly: This is the extreme version—70% fat, 25% protein, 5% carbs. Your body switches to using ketones (from fat) instead of glucose for energy. It’s not for everyone, but some people love it.

Flexible Dieting (IIFYM): Achieving Sustainable Adherence

Let’s talk about IIFYM, or “If It Fits Your Macros.” This is hands-down my favorite approach because it’s sustainable without making you feel like you’re living in food prison.

Here’s the deal: IIFYM means you can eat both the “good” stuff (chicken, broccoli, sweet potatoes) AND the “bad” stuff (donuts, pizza, ice cream) as long as it fits within your macro targets. Revolutionary, right?

The best way to do this is the 80/20 rule: Get 80% of your calories from nutrient-dense whole foods, and save the remaining 20% for whatever makes you happy. Want a cookie? Have a cookie. Just make it fit your macros.

Science backs this up too. Studies show that flexible dieting beats rigid dieting every time for long-term success. People who practice flexible dieting have less depression and anxiety, lose more fat over time, and are way less likely to eat excessively. Rigid diets? They usually lead to burnout and failure.

The core concept is simple: fat loss comes down to calories. You could eat nothing but Twinkies (please don’t) and lose weight if you’re in a deficit. But your macro breakdown affects how satisfied you feel, how well you maintain muscle, and how good you feel overall.

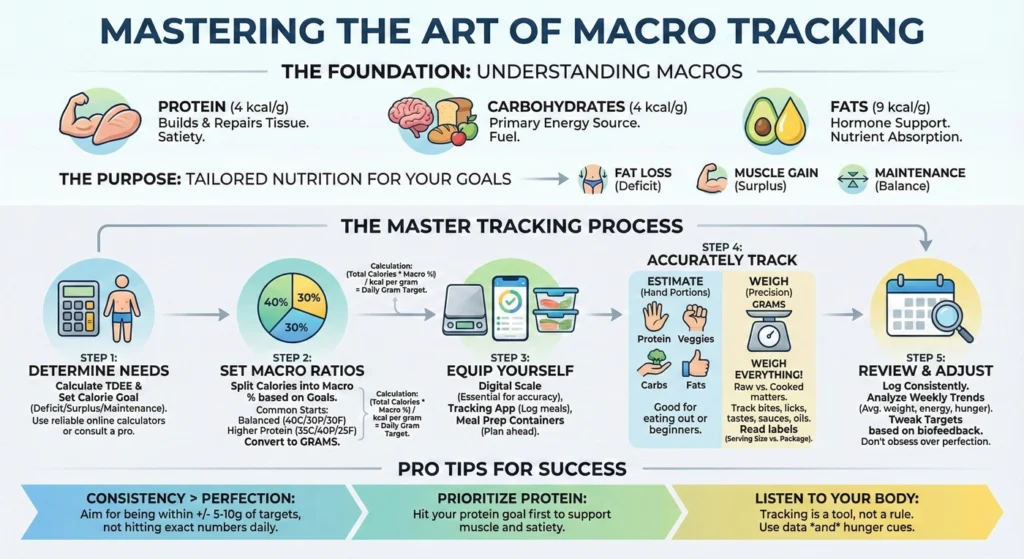

Mastering the Art of Macro Tracking: Tips for Accuracy and Consistency

Let me drop some real talk about tracking your macros—because if you’re going to do this, you might as well do it right.

Prioritize Accuracy: Weighing vs. Measuring

Buy a food scale. Seriously, just do it. They’re like $15 on Amazon and will change your life. Measuring cups are wildly inaccurate, especially for calorie-dense stuff.

Here’s what you need to know:

Weigh dry goods uncooked. That rice or pasta expands significantly when you cook it. The nutrition label is based on the dry, uncooked weight, so measure it before you cook it.

Weigh meat raw whenever possible. Meat loses water weight when you cook it, and the amount varies depending on your cooking method. For consistency, weigh it raw. If you must weigh it cooked, find a cooked entry in your tracking app.

Use the scale for everything solid. Cheese, nuts, meat, vegetables—weigh it all. Trust me on this one.

Utilize Tracking Tools

Get yourself a good tracking app. MyFitnessPal, MyMacros+, Lose It—pick one and use it religiously. These apps do all the math for you and have massive food databases. Life’s too short to calculate macros by hand.

Avoid Common Mistakes

Let me save you from the rookie mistakes I see all the time:

Don’t eyeball portions. Your brain is a terrible estimator, especially for things like peanut butter or olive oil. One tablespoon quickly turns into three if you’re not careful.

Track the licks, bites, and nibbles. That taste of cookie dough? Log it. The cheese you ate while making dinner? Log it. Those little bites add up to hundreds of calories.

Don’t forget cooking oils. Seriously, a tablespoon of oil is 120 calories. That’s a lot when you’re trying to hit your targets.

When eating out, overestimate. Restaurants use way more butter and oil than you think. Add at least 20% extra calories to whatever you’re logging, or better yet, find a similar meal that looks calorie-dense in your app.

Don’t “eat back” exercise calories. Your fitness tracker is probably overestimating how many calories you burned. Just stick to your planned intake.

Adjusting Macros for Health Conditions and Age

Not everyone fits into the same box, and that’s okay. Let’s talk about some special situations.

Age and Metabolism

Real talk: as you get older (we’re talking 40s and beyond), your metabolism slows down and you naturally lose muscle mass. Depressing, I know. The good news? You can fight back by prioritizing protein. Aim for the higher end of recommendations—30-35% of your daily calories. This helps you maintain strength and muscle as you age.

PCOS Management

Ladies with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome often deal with insulin resistance, which means carbs can be tricky. Many women with PCOS do better with lower carb intake—around 30-35% of calories—while bumping up lean protein and healthy fats. The healthy fats are especially important for hormone production.

Endurance Athletes

If you’re running marathons or doing long cycling sessions, carbs are your best friend. You need them to fuel those intense workouts and refill your glycogen stores afterward. But don’t skimp on protein—you still need about 1.8 g/kg for tissue repair and recovery.

The High Protein Caveat: Kidney Health Risk

Okay, here’s something important that doesn’t get talked about enough. While high-protein diets (over 1.5 g/kg per day) are super popular for weight loss, they might not be great for everyone. If you have existing kidney issues or risk factors for kidney disease, all that protein can put extra stress on your kidneys.

High protein intake can cause something called glomerular hyperfiltration—basically your kidneys work overtime initially, but over time this can actually damage them and increase your risk of proteinuria (protein in your urine, which is not good).

Here’s another interesting thing: where your protein comes from matters. Animal protein, especially red and processed meat, has been linked to higher risk of kidney disease compared to plant-based proteins. So if you’re concerned about kidney health, consider getting more protein from beans, lentils, tofu, and other plant sources.

Frequently Asked Questions

Let me answer the questions I get asked all the time:

What is the ideal macro ratio for fat loss?

While everyone’s different, a popular starting point for fat loss is around 40% protein, 30% carbs, and 30% fats. The key is keeping protein high (25-35%) to maintain muscle and keep you full. From there, adjust based on how you feel and your results.

Is tracking macros better than just counting calories?

Look, calories determine whether you gain or lose weight—that’s non-negotiable. But tracking macros is about quality, not just quantity. It ensures you’re getting enough protein to maintain muscle, enough carbs for energy, and enough fat for hormones and satiety. It’s a more complete picture of your nutrition.

Can I lose weight on a high-carb diet?

Absolutely! Weight loss is all about that calorie deficit. Studies comparing high-carb and low-carb diets with the same calories show basically identical weight loss. Choose the approach that makes you feel best and that you can stick to long-term.

What is IIFYM?

IIFYM stands for “If It Fits Your Macros,” and it’s a flexible dieting approach where you track your protein, carbs, and fats without completely cutting out foods you love. As long as you hit your macro targets and maintain your calorie goal, you can eat a wide variety of foods. It’s all about balance and sustainability.

Conclusion: Sustainability is the Key to Long-Term Success

Here’s the bottom line: counting macros for weight loss is a super personalized tool. What works for your friend might not work for you, and that’s totally normal. You’re going to need to experiment a bit based on your activity level, food preferences, health goals, and how your body responds.

The absolute best nutrition plan? It’s the one you can actually stick to for the long haul. Not for two weeks, not for a month—but for months and years. Make small adjustments every 2-4 weeks based on how you’re progressing and how you feel. Pay attention to your energy levels, your workouts, your mood, and your results.

And look, if you’re dealing with complex health issues or just feel overwhelmed by all this information, there’s zero shame in getting help from a Registered Dietitian or nutrition professional. They can create a personalized plan that takes into account your unique situation and goals.

At the end of the day, macros for weight loss isn’t about perfection—it’s about progress. Use a macro calculator for weight loss as a starting point, track your food honestly, adjust as needed, and most importantly, don’t beat yourself up if you have an off day. Life happens. Just get back on track the next meal.

Now go forth and conquer those macros!

References:

- Harris JA. A Biometric Study of Basal Metabolism in Man. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington; 1919. (digital.library.cornell.edu)

- Roza AM, Shizgal HM. The Harris Benedict equation reevaluated: resting energy requirements and the body cell mass. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;40(1):168–182. doi:10.1093/ajcn/40.1.168 (academic.oup.com)

- Mifflin MD, St Jeor ST, Hill LA, Scott BJ, Daugherty SA, Koh YO. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51(2):241–247. doi:10.1093/ajcn/51.2.241 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Frankenfield D, Roth-Yousey L, Compher C. Comparison of predictive equations for resting metabolic rate in healthy nonobese and obese adults: a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(5):775–789. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.005 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Frankenfield DC. Bias and accuracy of resting metabolic rate equations in non-obese and obese adults. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(6):976–982. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2013.03.022 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Weir JB de V. New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J Physiol. 1949;109(1–2):1–9. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004363 (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Tappy L. Thermic effect of food and sympathetic nervous system activity in humans. Reprod Nutr Dev. 1996;36(4):391–397. doi:10.1051/rnd:19960405 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Levine JA. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis: the crouching tiger hidden dragon of societal weight gain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):237–240. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL. Adaptive thermogenesis in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34(Suppl 1):S47–S55. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.184 (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Trexler ET, Smith-Ryan AE, Norton LE. Metabolic adaptation to weight loss: implications for the athlete. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11:7. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-11-7 (jissn.biomedcentral.com)

- Byrne NM, Sainsbury A, King NA, Hills AP, Wood RE. Intermittent energy restriction improves weight loss efficiency in obese men: the MATADOR study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(2):129–138. doi:10.1038/ijo.2017.206 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Institute of Medicine (US) Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. (AMDR ranges). (nationalacademies.org)

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2020–2025). Guidance to limit saturated fat to <10% of calories (age 2+). (dietaryguidelines.gov)

- Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D. Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis. Obes Rev. 2005;6(2):133–142. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00178.x (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Helms ER, Aragon AA, Fitschen PJ. Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11:20. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-11-20 (jissn.biomedcentral.com)

- Morton RW, Murphy KT, McKellar SR, et al. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training–induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(6):376–384. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-097608 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Longland TM, Oikawa SY, Mitchell CJ, Devries MC, Phillips SM. Higher compared with lower dietary protein during an energy deficit combined with intense exercise promotes greater lean mass gain and fat mass loss: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(3):738–746. doi:10.3945/ajcn.115.119339 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Krieger JW, Sitren HS, Daniels MJ, Langkamp-Henken B. Effects of variation in protein and carbohydrate intake on body mass and composition during energy restriction: a meta-regression. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):260–274. doi:10.1093/ajcn/83.2.260 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Chaston TB, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Changes in fat-free mass during significant weight loss: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:743–750. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803483 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Gardner CD, Trepanowski JF, Del Gobbo LC, et al. Effect of Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss (DIETFITS). JAMA. 2018;319(7):667–679. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0245 (jamanetwork.com)

- Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(3):147–157. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00005 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Lichtman SW, Pisarska K, Berman ER, et al. Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(27):1893–1898. doi:10.1056/NEJM199212313272701 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults (e.g., 500–1,000 kcal/day deficit; 1,000–1,200 kcal women / 1,200–1,500 kcal men as common LCD ranges; VLCD <800 kcal/day not recommended without special conditions). (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: Nutrition and athletic performance. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(3):501–528. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2015.12.006 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Symons TB, Sheffield-Moore M, Wolfe RR, Paddon-Jones D. A moderate serving of high-quality protein maximally stimulates skeletal muscle protein synthesis in young and elderly subjects. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(9):1582–1586. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2009.06.369 (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Institute of Food Technologists (IFT). The lowdown on sugar substitutes (table of sugar alcohol energy values; e.g., xylitol ~2.4 kcal/g, maltitol ~2.1 kcal/g, sorbitol ~2.6 kcal/g, erythritol ~0.2 kcal/g). 2019. (ift.org)